COGNITIVE APPROACH

OUTLINE OF THE COGNITIVE APPROACH

The cognitive approach: the study of internal mental processes, the role of schema, the use of theoretical and computer models to explain and make inferences about mental processes. The emergence of cognitive neuroscience.

The Cognitive Revolution began in the mid-1950s when researchers in several fields began to develop theories of mind based on complex representations and computational analogies (Miller, 1956; Broadbent, 1958; Chomsky, 1959; Newell, Shaw, & Simon, 1958)

THE COGNITIVE APPROACH: OPENING THE "BLACK BOX"

Cognitive psychologists believe understanding "what goes on inside the mind" is key to making sense of human behaviour. They focus on the mental processes that shape our actions and thoughts, looking beyond observable behaviours to explore the mind's inner workings.

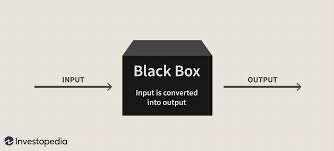

The cognitive approach emerged as a response to the limitations of behaviourism, which dominated psychology in the early 20th century. Behaviourists like B.F. Skinner insisted that studying mental processes was futile since they couldn’t be observed or measured. They treated the mind as a "black box"—an unknown and unknowable space—arguing that all behaviour could be explained through environmental stimuli and responses. For behaviourists, the focus was on observable actions rather than the invisible processes driving them.

Cognitive psychologists challenged this view, arguing that the mind isn’t a mysterious black box but an intricate and essential part of understanding behaviour. They recognised that humans aren’t just passive responders to the environment but active information processors. This approach opened the door to exploring how we think, learn, remember, and make decisions.

WHAT DOES THE COGNITIVE APPROACH STUDY?

The cognitive approach primarily focuses on developing theoretical models that simulate mental processes in a way that mirrors how the biological brain functions. Cognitive psychologists believe that internal thought processes can be understood by breaking them down into their components, such as memory, attention, perception, and language

MEMORY: How we store, retrieve, and use information over time.

ATTENTION: How we focus on certain stimuli while ignoring others.

PERCEPTION: How we interpret sensory information to understand our environment.

LANGUAGE AND SPEECH: How we communicate ideas and interpret meaning.

PROBLEM-SOLVING AND PLANNING: How we think ahead and find solutions to challenges.

FACE RECOGNITION: Identifying and remembering individual faces is a key skill in social interaction.

SELF-AWARENESS AND SELF-RECOGNITION: How we perceive ourselves as unique individuals.

CONSCIOUSNESS: The broader awareness of our thoughts, surroundings, and existence.

These processes combine to create complex abilities that define what it means to be human-like recalling a vital memory, recognising a familiar face, or planning for the future. Cognitive psychologists aim to understand how these mental processes work individually and how they interact to shape behaviour and contribute to our sense of self.

DOES THE COGNITIVE APPROACH REPLACE BEHAVIOURISM?

While the cognitive approach focuses on investigating internal mental processes, this does not mean behaviourism is no longer relevant. Cognitive psychology and behaviourism have distinct focuses and methodologies but complement rather than replace one another.

Cognitive psychology prioritises understanding how we process, store, and retrieve information, exploring concepts like memory, perception, and problem-solving. However, it does not dismiss the importance of learning from the environment—a cornerstone of behaviourism. Instead, it provides a broader perspective by incorporating how internal processes interact with external stimuli to shape behaviour.

DIFFERENT FOCUS, NOT REPLACEMENT

Behaviourism, emphasising observable behaviours and environmental influences, remains valuable in explaining how people learn through reinforcement, punishment, and conditioning. Its practical applications in education, therapy, and habit formation remain widely used. Cognitive psychology, on the other hand, delves into the “black box” of the mind, addressing aspects of human experience behaviourism does not, such as thought patterns, decision-making, and attention.

WHY DOES THE COGNITIVE APPROACH MATTER?

The cognitive approach has profoundly impacted psychology, influencing everything from education to artificial intelligence. It helps explain how we process and use information, why we remember some things but forget others, and how we solve problems or make decisions. Significantly, it shifted the focus of psychology back to the mind, showing that human behaviour can’t be fully understood without exploring the internal processes that guide it.

By opening up the "black box," cognitive psychology has provided a richer, more nuanced understanding of what it means to think, learn, and be human. It reminds us that the mind isn’t just a passive recipient of the world but an active participant in creating our reality.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY AND NEUROSCIENCE

While neuroscientists focus on the brain’s chemical and genetic foundations, cognitive psychologists are more concerned with understanding how mental processes function. Cognitive psychology uses models and experiments to explore how different brain systems interact to create cognition, concentrating on integrating cognitive tasks that form the mind rather than delving into the underlying biological mechanisms.

This approach investigates how we process, store, and retrieve information, aiming to understand how these mental processes shape behaviour and help us interpret the world around us. Cognitive psychology offers insights into how we think, learn, and adapt by focusing on the function of cognition rather than its biological origins.

THEORETICAL MODELS

Theoretical models in cognitive psychology aim to explain how different mental processes work together as an interconnected system. These models explore functions such as memory, language, perception, attention, and decision-making, illustrating how the brain coordinates these processes to produce behaviour and thought.

HOW COGNITIVE SYSTEMS WORK TOGETHER

Cognitive systems function as a network, each performing a specific role while interacting with others to achieve complex tasks. For example:

Memory and Language: Work together to retrieve and articulate knowledge.

Attention and Perception: Help focus on and interpret sensory information, like recognising a familiar face in a crowd.

Decision-Making and Problem-Solving: Rely on information from memory and attention to evaluate options and make choices.

These processes occur seamlessly, but theoretical models break them down to study their roles and how they combine to enable behaviour.

UNDERSTANDING SYSTEM INTERACTIONS THROUGH MODELS

Theoretical models in cognitive psychology aim to simplify and explain complex mental processes by breaking them down into systems and components. These models help psychologists ask and answer critical questions to understand better how mental processes function and interact.

A good theoretical model asks questions such as:

What is the system? For example, is the system being studied memory, attention, or perception?

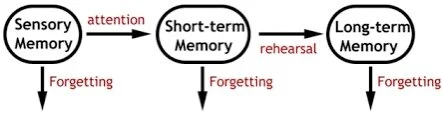

What are the components of the system? In the case of memory, these might include short-term memory, long-term memory, and sensory memory.

How does the system work? For instance, how does attention select crucial sensory information and ensure it is temporarily stored in short-term memory?

How does the system interact with other systems? For example, how does memory work with language systems, such as Broca's area, to retrieve and structure words for communication?

EXAMPLE 1: READING A BOOK

Reading a book involves several interconnected systems working together:

Perception: The visual cortex processes written text, identifying letters and words.

Language Systems: Wernicke’s area decodes the meaning of the words, while Broca’s area constructs an internal dialogue or vocalises the text.

Memory: Semantic memory retrieves the meanings of words while working memory holds the sentence structure to make sense of the text as a whole.

Attention: Maintains focus on the text, filtering out distractions like background noise.

This seamless integration of systems allows us to understand complex narratives and retain information.

EXAMPLE 2: SPEAKING AND BROCA'S AREA

Language production highlights the interaction between systems, particularly the role of Broca’s area in coordinating speech. Consider answering a question in conversation:

Attention: Focuses on the speaker’s question, ignoring irrelevant sounds.

Perception: Processes the auditory input in the auditory cortex, then Wernicke’s area interprets the question’s meaning.

Memory: Long-term memory retrieves relevant vocabulary and grammar rules for the response.

Broca’s Area: Organises the retrieved words into a grammatically correct sentence.

Motor Systems: The motor cortex activates the tongue, lips, and vocal cords to articulate the response.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN A SYSTEM IS DAMAGED?

When Broca’s area is damaged, it leads to Broca’s aphasia, a condition where speech production is impaired. Individuals with Broca’s aphasia:

Have difficulty forming complete sentences, often speaking in broken or fragmented phrases.

Can still understand language, as Wernicke’s area remains functional.

Highlight the importance of Broca’s area as part of the more extensive language system.

WHY MODELS MATTER

Theoretical models allow cognitive psychologists to explore how different systems work together, providing insights into both normal and impaired cognition. These models help us understand the intricate mechanisms underlying human behaviour and cognition by breaking down complex processes like reading and speaking.

THE MULTI-STORE MODEL

THE MIND-AS-COMPUTER METAPHOR

Cognitive psychology often compares the human mind to a computer, drawing parallels between how both systems process information. Just as a computer stores, retrieves, and processes data to produce an output, humans follow similar mechanisms in their mental operations. This “MIND-AS-COMPUTER” METAPHOR forms a cornerstone of the cognitive approach, providing a framework for understanding mental processes.

Key comparisons include:

STORAGE AND RETRIEVAL: Humans store memories in short-term and long-term memory, akin to how computers use RAM and hard drives.

PROGRAMMING: Just as a computer follows coded instructions, humans rely on mental "programmes" or schemas to interpret and respond to their environment.

INPUT AND OUTPUT: Sensory information serves as input, which cognitive systems process to generate behavioural or verbal responses as output.

This metaphor has been instrumental in guiding research and developing theoretical models that explain how humans process information systematically. However, it also has limitations, as the mind’s emotional, social, and creative aspects extend far beyond the capabilities of a machine.

THE MIND AS COMPUTER METAPHOR

RESEARCH METHODS USED IN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Given that cognitive psychologists study the “Blackbox”, the next logical question is how do they study the box the behaviourists said wouldn’t open? In other words, how do they explore the holy of holies, thought itself?

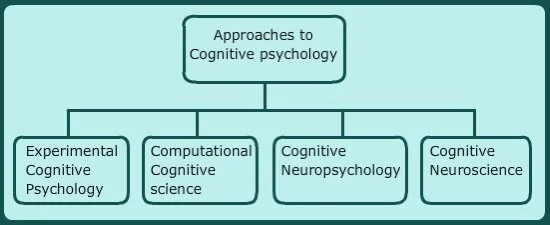

Cognitive psychology, in its modern form, incorporates a remarkable set of new technologies in psychological science. It uses four research domains to research the brain:

Experimental cognitive psychology

Cognitive computer science

Cognitive neuropsychology:

Cognitive neuroscience

THE FOUR RESEARCH DOMAINS

COGNITIVE NEUROPSYCHOLOGY:

Cognitive neuropsychology has its roots in the 1800s, long before it became a formally recognised approach. Cognitive neuropsychology studies people with brain damage to deduce how the neurotypical brain works. Examples of cognitive neuropsychology include KF, HM, Phineus Gage, Tan (Paul Broca), Clive Wearing, Charles Whitman, and many more. For instance, Paul Broca famously linked speech production to a specific brain area by studying patients with language deficits and confirming the damage through post-mortem analysis. Similarly, cases like Phineas Gage revealed how frontal lobe injuries could alter personality and decision-making.

Before modern scanning technologies, researchers relied on post-mortem examinations, waiting until patients with brain injuries had passed away to examine their brains for damage. During the patients’ lifetimes, psychologists gathered clues through careful observation and clinical interviews, piecing together how specific injuries affected behaviour and cognition.

Today, with advanced neuroimaging techniques like MRI and CT scans, cognitive neuropsychologists can study brain damage in living patients with much greater precision. These technologies allow researchers to map cognitive deficits to specific brain areas without waiting for post-mortem confirmation, making it easier to understand how various brain parts work together to support cognitive functions.

Cognitive neuropsychology remains a vital tool for exploring how the brain operates.

EXPERIMENTAL COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

The experimental method was the primary approach used in cognitive psychology before the advent of cognitive neuroscience. Emerging in the 1950s, when technology lacked the sophistication for direct brain analysis, this method relied on creating and testing theoretical models to understand mental processes.

THEORETICAL MODELS AND TESTING

Cognitive psychologists begin by formulating a theoretical model of a specific mental function. For example, they might explore how perception is organised into schemata. Researchers then use reasoning to develop their theories, but unlike earlier philosophers, they don’t stop at theoretical conclusions. Instead, they test these models through controlled experiments.

Experiments are usually conducted in laboratories, providing controlled environments for precise data collection and analysis. Once the results are analysed, cognitive psychologists decide whether to accept or reject their initial ideas. The scientific nature of this process has been critical in advancing our understanding of human cognition.

NOTABLE EXPERIMENTS IN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Many foundational studies in cognitive psychology highlight the experimental method’s strength:

Baddeley and Hitch (1974) Developed the working memory model, proposing components like the phonological loop and episodic buffer.

Loftus and Palmer (1974): Explored how leading questions distort memory recall in eyewitness testimony.

Miller (1956) Proposed the "magic number seven," identifying the limited capacity of short-term memory.

Peterson and Peterson (1959) Demonstrated the rapid decay of information in short-term memory without rehearsal.

Bartlett (1932): Investigated reconstructive memory using “The War of the Ghosts,” showing how cultural schemata influence recall.

Piaget (1936): Examined cognitive development in children, providing a framework for understanding learning stages.

These experiments exemplify how experimental cognitive psychology tests theoretical models with neurotypical individuals who are skilled performers in the cognitive subdomain being studied.

EVALUATION OF EXPERIMENTAL COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

While experimental methods have driven significant progress in understanding mental processes, they also have limitations:

External Validity: Experiments often lack mundane realism and ecological validity, as laboratory settings may not reflect real-world experiences.

Population Validity: Many studies use narrow samples (e.g., university students), leading to ethnocentric findings and an imposed etic that may not generalise to diverse populations.

Biological Correlations: This approach doesn’t reveal the physical brain regions involved in specific mental processes, a gap that cognitive neuroscience later addressed.

Despite these issues, the experimental method remains a cornerstone of cognitive psychology, offering critical insights into human cognition and behaviour. It has laid the foundation for integrating cognitive models with neuroscience, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of mental processes.

COGNITIVE COMPUTER SCIENCE:

The computation of the human mind, behaviour, and the links between natural and artificial intelligence. Computational models are closely akin to a branch of computer science called artificial intelligence. Programmers build computational models to represent human cognitive processes.

Evaluation: It’s a systematic way of investigating mental processes, but it cannot be regarded as a representation of the exact cognitive mechanisms involved,

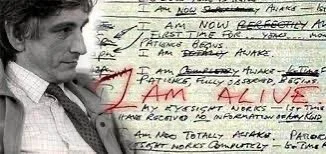

CLIVE WEARING AN AMNESIAC WITH NO ABILITY TO FORM NEW MEMORIES, FREQUENTLY BELIEVED THAT HE HAD ONLY RECENTLY AWOKEN FROM A COMATOSE STATE

Evaluation: Individuals may have a unique brain organisation so case studies are not generalisable. This method of study has been very useful in the past when technology was not available, e.g., FMRI and PET scans. Not great at deciphering higher cognitive functions such as reasoning and decision-making or where cognitive functions and processes do overlap. Real-time activity in the brain cannot be measured.

COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE:

THE BRAIN IN LOVE

COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE

Cognitive neuroscience primarily focuses on studying the biological processes underlying cognition in neurotypical individuals, aiming to map mental processes to specific brain regions and pathways. In essence, it explores the biology behind cognitive psychology, using advanced technology to determine where and when these processes occur in the brain.

Methods Used in Cognitive Neuroscience:

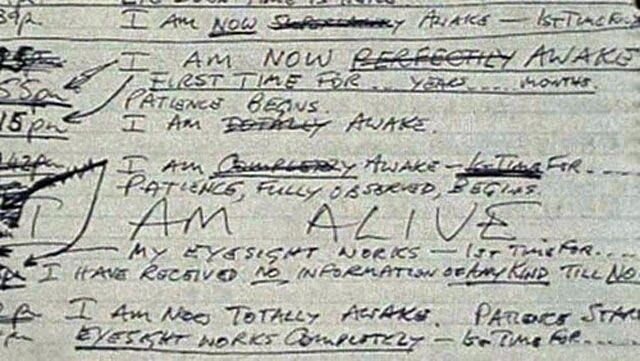

Functional Neuroimaging: Techniques like fMRI and PET scans to observe which brain regions are active during particular cognitive tasks.

Electrophysiology: Using EEG to measure electrical activity in the brain and track rapid changes in neural function.

Experimental Psychology: Employing tasks and stimuli to link mental processes with brain activity.

Cognitive Genomics and Behavioural Genetics: Investigating how genetic factors influence brain function and cognitive abilities.

These methods allow cognitive neuroscientists to study processes like memory, language, attention, and perception in individuals with typical brain functioning, providing a baseline for understanding cognition.

Evaluation:

While cognitive neuroscience has provided groundbreaking insights, it also has limitations:

Focus on Neurotypical Individuals: By primarily studying those without brain injuries or disorders, it may overlook variations in cognition caused by atypical brain function.

Poor Spatial or Temporal Resolution: Some techniques struggle to capture fine details of brain activity or measure changes in real time.

Limited Behavioural Scope: Imaging techniques may not fully capture complex or nuanced behaviours.

Participant Discomfort: Scanning methods like fMRI require participants to remain still in enclosed spaces, which can be uncomfortable or unnatural.

Despite its limitations, cognitive neuroscience is a cornerstone of modern psychology, offering a biological lens to understand how neurotypical brains support complex mental processes

CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE COGNITIVE APPROACH

Contemporary cognitive neuroscience has increasingly looked towards the brain to explain the inner workings of the human mind; this is most evident with the rise of cognitive neuroscience’s use of neuro-imaging. This method has, however, been met with mixed reactions. On the one hand, classical cognitive scientists—in the experimental and computational traditions—have argued that cognitive neuroimaging does not, and cannot, answer questions about the cognitive mechanisms responsible for creating intelligent behaviour. Neuro-imaging does not tell us enough about mental processes, which means that the researcher has to make inferences that may involve subjectivity. For example, Savage-Rumbaugh measured sign language acquisition in a bonobo chimpanzee named Kanzi but in reality, neuro-imaging can't reveal what Kanzi or any other “great ape” is thinking, it is limited to information about the neural basis of cognition.

Thus, some researchers still see a distinction between the two approaches, e.g., that cognitive psychology is more focused on information processing and behaviour, and cognitive neuroscience studies the underlying biology of information processing and behaviour. But others argue …. “that cognitive neuroscience is the integration of at least four areas that emphasise mental functions, not brain. In other words, it is not as concerned with biology as neuroscience is. It is concerned with creating computer models to simulate mental behaviour in a way that resembles the biological mind..” Richard Ivry, of UC Berkeley.

TO DEMONSTRATE THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE AND NEUROSCIENCE

COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE USES SCANS TO INVESTIGATE MENTAL FUNCTIONS

NEUROSCIENCE USES SCANS TO INVESTIGATE BIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS

The four disciplines emerged as technology advanced better ways of investigating the brain. But all the research domains of cognitive science have exactly the same objective, with the bottom line being that they all want to discover the same underlying principles. The only difference between these domains is how they investigate their theories.

STEVEN PINKER IS A CANADIAN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGIST & SCIENCE AUTHOR

Many criticisms of cognitive psychology tend to focus on the techniques used by experimental cognitive psychologists, e.g., laboratory studies with contrived tasks that have little to do with everyday behaviour in their natural settings. Such studies tend to use methods to test phenomena that people would be unlikely to face in real life, such as learning digital sequences to test long-term memory. Issues of external validity, such as lack of mundane realism and ecological validity, therefore, are common.

STUDYING A FISH OUT OF WATER HAS NO EXTERNAL VALIDITY

But criticising cognitive psychology for the practices of one of their subdomains is like "chucking the baby out with the bathwater", an idiomatic expression for an avoidable error in which something good is eliminated when trying to get rid of something bad as, ultimately, cognitive psychology uses many other research methods to investigate their theories, such as cognitive neuroscience, cognitive neurology and cognitive computer science. Methods such as these use a variety of rigorous procedures to collect and evaluate evidence. This is a significant strength of this approach as it triangulates and supports the criticism of artificiality so often levied at experimental cognitive psychology. All the research domains have limitations (see above), but when you combine their findings, the conclusions become very robust. For example, Baddeley’s dual-task experiment was supported by clinical case studies of brain-damaged people like HM and KF and also endorsed by PET scans.

Overall, research from the cognitive sciences is very well regarded by the scientific community as it is empirically sound.

Other evaluations devalue the analogy between the human mind and the operations of a computer (inputs and outputs, storage systems, the use of a central processor) because they believe there is a vast difference between information processing, which occurs with machines and organic biological structures such as the human mind. For example, the human mind is more prone to errors, forgetting or “retrieving” incorrect information from memories, which computers do not do. Also, humans are affected by emotions, hormones and life events. Therefore, basing cognitive processes on computer-based understanding lacks validity as it may not be a proper fit for how the human mind actually works.

ARE WE MORE THAN THIS?

The Cognitive Approach may be considered reductionist, as it does not provide a full explanation of human behaviour; it ignores some biological and social contributors, like emotions and parenting. For example, Baron-Cohen's research into autism ignored other issues such as hormone levels.

Cognitive psychology sits on the soft determinist fence and, therefore, represents a middle ground between hard determinism and free will. It views people as having a choice that is not totally constrained by external or internal factors. For example, the cognitive approach acknowledges that all actions have causes as actions are confined by the limits of a biological system; for example, dogs can’t talk no matter how much you submerge them in languages and humans can’t perceive ultraviolet light. Thus, cognitive psychologists accept that humans are limited in making some choices because of the way they are designed to process information. However, cognitive psychologists believe there is some conscious mental control over behaviour.

IMPRISONED OR FREE?

On the plus side, this view is quite refreshing because apart from humanism, all the other psychological approaches are hard determinism which is quite a depressing and fatalistic view of life. At least a soft determinist view recognises that individuals still have a part to play in causality and can be blamed or praised. For their behaviour. On the negative side, hard determinists criticise cognitive psychologists for failing to realise the extent to which freedom is limited. They also point out that it is difficult to draw a line on what is and isn’t a determining factor in human choices. Moreover, is it determinism if it allows freedom?

B.F. Skinner criticised the cognitive approach as he believed that only external stimulus-response behaviour could be scientifically measured. More importantly, he thought the mediation processes between stimulus and response, e.g., the black box, did not exist and were thus irrelevant. Paradoxically, recent research from the field of cognitive neuroscience has shown that the human brain makes up its mind up to ten seconds before an individual is cognisant of a decision. The neuroimaging of participants making decisions revealed that researchers could predict what choice people would make before the subjects were even aware of having made a decision. So perhaps Skinner and the other early behaviourists were right, after all, and maybe the blackbox isn’t that relevant.

It should be noted, that this finding does not mean that it is still not important to study mental processes, it just means that consciousness may not be as valuable as the early cognitive psychologists thought.

STEREOTYPES CAN BE CHALLENGED WHEN YOU UNDERSTAND SCHEMA THEORY

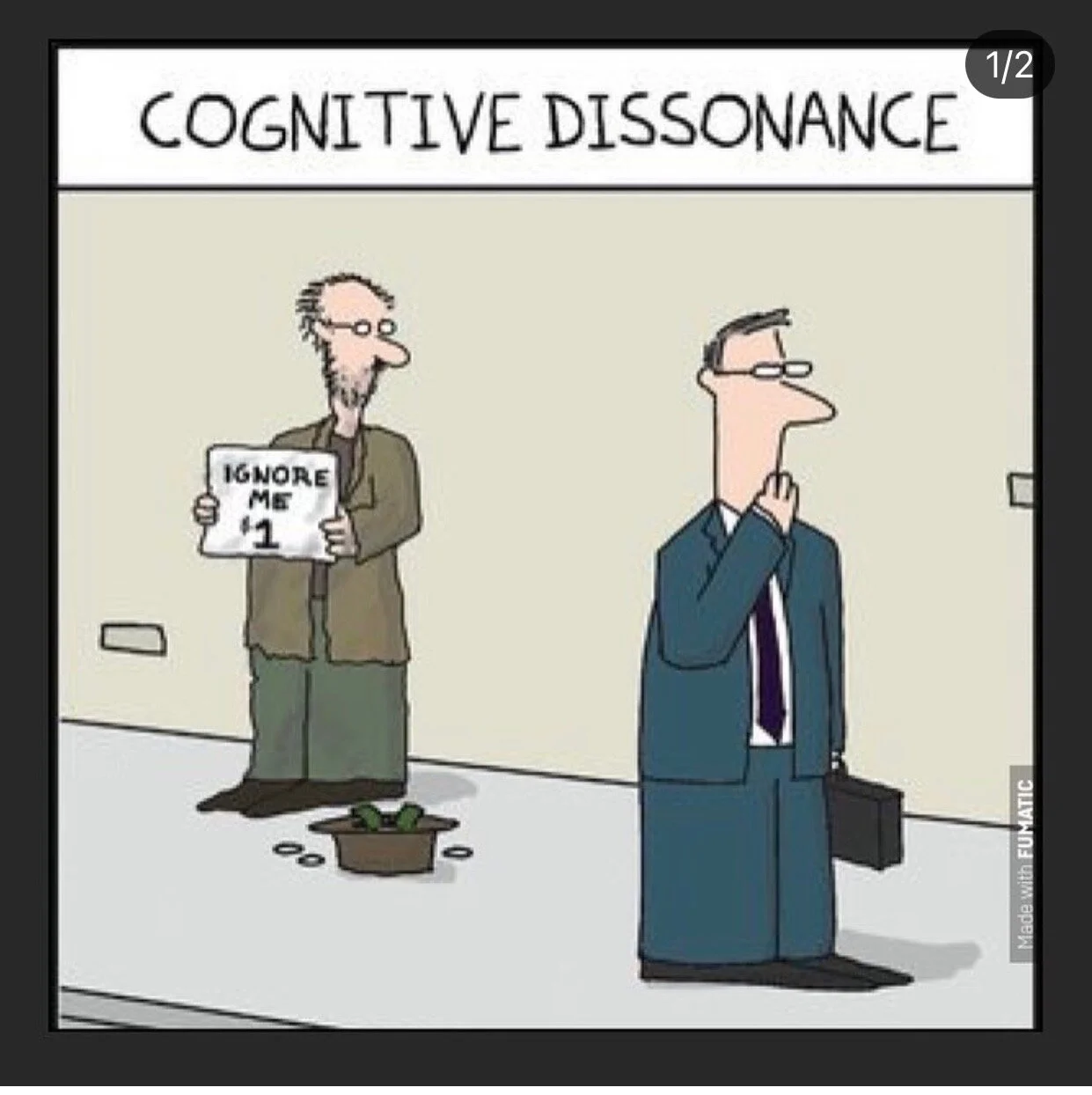

But in summing up, the cognitive approach is probably the most dominant in psychology today. It has been applied to a wide range of practical and theoretical contexts that can be applied in various areas of psychology. For example, the cognitive approach has helped us better understand how people form impressions of others via schemata, and how cognitive biases such as heuristics and cognitive dissonance can distort our thinking.

Cognitive dissonance is a theory that refers to the mental conflict that occurs when a person's behaviors and beliefs do not match

When applying the cognitive approach to psychopathology, it has also highlighted that dysfunctional behaviour might be due to faulty or irrational thought processes and how cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been very effective for treating these dysfunctional thoughts, e.g., depression and anxiety (Hollon & Beck, 1994).

The cognitive approach has also helped improve childcare, education and eyewitness testimony. For example, in Loftus and Palmer's study of memory, findings suggested that police officers need to avoid using leading questions when interviewing witnesses, as this may alter the memory of the witnesses.

Lastly, Cognitive science integrates with many other approaches and areas of study to produce, for example, social learning theory, evolutionary psychology, neuroscience and artificial intelligence (AI).

COGNITIVE BIASES

GENERALISATIONS

A bias is a disproportionate weight in favour of or against an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individual, a group, or a belief. In science and engineering, a bias is a systematic error.

Stereotype: a widely held but fixed and oversimplified image or idea of a particular type of person or thing, "the stereotype of the woman as the carer".

Schema (singular) schemata (plural): In psychology and cognitive science, a schema describes a pattern of thought or behaviour that organizes categories of information and the relationships among them. A schema is a workflow or storyboard that tells you what to do in a recurring situation. For example, when you go shopping, you might follow an internal script to make shopping more efficient: you pick the same products in the same sequence every time. You know in advance what you will buy; there are no decisions involved; in fact, you ignore all alternative products. A schema allows you to navigate familiar, recurrent, and similar situations by following the same sequence of actions.

A heuristic is a mental shortcut that our brains use that allows us to make decisions quickly without having all the relevant information. They can be thought of as rules of thumb that allow us to make a decision that has a high probability of being correct without having to think everything through.

A heuristic consists of preferences that help you decide when you do not have enough information or do not care enough to make an informed decision. For example, when you want to buy yogurt but are no nutritionist, you might decide on which yogurt you buy by the familiarity of the brand name (you prefer the familiar; this is called the familiarity heuristic) and other aspects that have nothing to do with the yogurt itself.

Certainly! Heuristics are mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that individuals use to simplify decision-making and problem-solving. There are several types of heuristics, and they can be categorized into different groups. Here are some common types:

Availability Heuristic: People tend to rely on information that is readily available or easily recalled from memory. If something comes to mind easily, it is perceived as more common or important.

Representativeness Heuristic: This heuristic involves making judgments based on how well an object or situation matches a prototype. It categorises things based on how similar they are to a typical example.

Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic: It involves starting with an initial estimate (the anchor) and then adjusting it based on additional information. The initial anchor can significantly influence the final judgment.

Simulation Heuristic: People often assess the likelihood of events based on how easily they can imagine or mentally simulate the outcome. If an event is easy to picture, it may be perceived as more likely.

Substitution Heuristic: When faced with a difficult question, individuals may substitute an easier question and answer that instead. This allows for quicker decision-making, even if the substituted question is irrelevant.

Affect Heuristic: Emotional responses or feelings can influence decision-making. People may rely on their emotional reactions to judge the desirability or riskiness of an option.

Base Rate Heuristic: This involves using general information about the likelihood of an event occurring (base rate) and adjusting it based on specific information about the case at hand.

Hindsight Bias: After an event has occurred, people tend to perceive the outcome as having been more predictable than it actually was. This bias can influence the way decisions are evaluated retrospectively.

Confirmation Bias: This is not exactly a heuristic but is a related cognitive bias. It involves the tendency to search for, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms one's preexisting beliefs.

These heuristics can be useful for making quick decisions, but they can also lead to errors and biases in judgment. It's important to be aware of them and consider them critically in decision-making processes.

A LIST OF COGNITIVE BIASES

Unconscious bias: An unconscious bias (also called Implicit bias) refers to attitudes and beliefs that occur outside of our conscious awareness and control.

Identity politics: the tendency for people of a particular religion, race, social background, etc., to form exclusive political alliances, moving away from traditional broad-based party politics.

Cancel culture or a call-out culture is a modern form of ostracism in which someone is thrust out of social or professional circles – whether it be online, on social media, or in person. Those subject to this ostracism are said to have been "cancelled”

Affect Heuristic: Why we tend to rely upon our current emotions when making quick, automatic decisions.

Ambiguity Effect: Why we prefer options that are known to us

Anchoring Bias: Why we tend to rely heavily upon the first piece of information we receive

Attentional Bias: Why do our perceptions change based on what we commonly think about?

Availability Heuristic: Why we tend to think that things that happened recently are more likely to happen again.

Bandwagon Effect: Why do people prefer popular options?

Base Rate Fallacy: Why we rely on event-specific information over statistics.

Bottom-Dollar Effect: Why we are more likely to be dissatisfied with that product than we otherwise would be.

Bounded Rationality: Why our decisions may not be optimal and are limited by time, information, and mental capacity.

Bundling Bias: Why we are more likely to consume our purchases over a bundle purchase. Why are we more likely to consume our individual purchases over a bundle purchase?

Bye-Now Effect: Why, when we read homophones, are we still primed by the other meaning of the word?

Cashless Effect: Why we're willing to pay more when no cash is involved in a transaction.Why we're willing to pay more when no cash is involved in a transaction.

Category Size Bias: Why do we perceive an option as more likely if it belongs to a large category than if it is in a small category?

Choice Overload Bias: Why we tend to have difficulty making choices when faced with many options.

Cognitive Dissonance: Why we tend to prefer having consistency in our beliefs (cognitions).

Commitment Bias: Why do people support their past ideas, even when presented with evidence that they're wrong?

Confirmation Bias: Why we interpret information favouring our existing beliefs.

Decision Fatigue: Why making many decisions reduces our ability to make rational ones.

Declinism: Why we feel the past is better compared to what the future holds

Decoy Effect: Why a third, inferior option can change how we decide between two similar-valued options.

Default Bias: Why we generally prefer to keep situations as they currently are

Distinction Bias: Why we tend to view two options as more distinctive when evaluating them simultaneously than separately.

Dunning–Kruger Effect: Why incompetent people fail to recognize their incompetency.

Empathy Gap: Why we tend to mispredict behaviours based on our emotional state.

Endowment Effect: Why we value our possessions more highly than the possessions of others.

Extrinsic Incentive Bias: Why do people think that extrinsic incentives are more motivating for others?

Extrinsic Incentive Bias: Why do people think that extrinsic incentives are more motivating for others?

Forer Effect: Why we tend to accept any personality feedback as true, regardless of validity.

Framing Effect: Why option presentation changes our decision-making.

Functional Fixedness: Why it's difficult to see any way to use objects besides their standard use.

Fundamental Attribution Error: Why we favoUr our judgment regardless of situational influences when explaining other's behaviour.

Gambler’s Fallacy: Why we tend to think an event is less likely to happen again if it happened several times in the past

Google Effect: Why we seem to forget information easily

Halo Effect: Why First Impressions Last

Hard–easy Effect: Why do we tend to overestimate our ability to do something considered hard and underestimate our ability to do something considered easy?

Hindsight Bias: Why we tend to see events as being more predictable than they truly were after the event occurred.

Hot-hand Fallacy: Why we experience a series of positive outcomes for a random event and tend to predict that future outcomes will also be positive.

Hyperbolic Discounting: Why we value immediate rewards more than long-term rewards.

Identifiable Victim Effect: Why we act to help specific groups even though others need help as well

IKEA effect: Why do we place a disproportionately high value on things we helped to create?

The illusion of Control: Why we often overestimate our ability to influence events.

The illusion of Validity: Why are we overconfident in our predictions?

Illusory Correlation: Why we assume a correlation between two variables

Illusory Truth Effect: Why we are more likely to believe that something is true if it is repeated to us enough times.

In-group Bias is the reason we tend to give favourable treatment to people who belong to the same groups as we do.

Incentivization: Why we tend to gravitate to working towards perks

Just-world Hypothesis: Why do we believe that all morally good actions add up to a reward and all morally bad actions add up to a punishment

Lag Effect: Why short lessons may not be a good ideas

Law of the Instrument: Why we tend to apply a skill/tool anywhere

Less-is-better Effect: Why we prefer the smaller or the lesser alternative

Levelling and Sharpening: Why we lose certain details of our memory and why we remember some

Levels-of-processing Effect: Why repetition improve memory retention

Look-elsewhere Effect: When a statistically significant observation should be overlooked.

Loss Aversion: Why is the pain of losing felt twice as powerfully compared to equivalent gains?

Mental Accounting: Why we treat one’s money differently

Mere Exposure Effect: Why does being exposed to something or someone make us view that thing or person more positively

Motivating-Uncertainty Effect: Why rewards of uncertain size tend to motivate us more than known rewards

Naive Allocation: Why we tend to prefer spreading limited resources evenly across options.

Negativity Bias: Why negative occurrences tend to have a greater impact on our psychological state than positive ones

Noble Edge Effect: Why we tend to favour brands that show care for societal issues

Nostalgia Effect: How our view of a rosy past can dictate our actions now

Observer-expectancy Effect: Why observers tend to unconsciously influence the behaviours of those they observe.

Omission Bias: Why we tend to react more strongly to harmful actions

Optimism Bias: Why people tend to underestimate their chance of experiencing adverse effects.

Ostrich EffectWhy we avoid dangerous or negative information

Peak-end Rule: Why we tend to judge an experience on how we felt at its peaks and its end

Pessimism bias: Why do some people overestimate the probability of negative events occurring

Planning Fallacy: Why we tend to underestimate the time we will need to complete a task when planning for it

Primacy Effect: Why is the first presented to us will be more easily recalled than the rest?

Priming Effect: Why unrelated stimuli can cause us to make different decisions than we normally would

Projection Bias: Why do we think our current preferences will remain the same in the future?

Reactive Devaluation: Why we often tend to devalue proposals made by people who we consider to be adversaries

Regret Aversion: Why we choose the option that minimises regret even if it's not optimal

Response Bias: Why responses to a survey or experiment can be inaccurate due to the nature of the survey or experiment

Restraint Bias: Why we tend to overestimate our control over impulsive behaviours

Rosy Retrospection: Why do we only remember the positive elements of our past:

Salience Bias: Why do we focus on more prominent things and ignore those that are less so?

Self-serving Bias: Why people overestimate their contribution to any outcome

Sexual Overperception Bias: Why men sense sexual interest when there is none and miss sexual interest when there is

Social Norms: Why do we try to act similarly to communities we are in

Source Confusion: Why we forget where our memories come from, and thereby lose our ability to distinguish the reality or likelihood of each memory.

Spacing Effect: Why information learned repeatedly is better retained when learned farther apart.

Spotlight Effect: Why is there a tendency to feel like all eyes are looking at us

Suggestibility: Why our memories can be changed by the suggestions of others

Survivorship Bias: Why we misjudge groups by only looking at specific group members

Telescoping Effect: Why recent events are thought to be longer ago than they were, and remote events thought to be more recent

Zero Risk Bias: Why do we prefer to eliminate one category of risk, even if doing so increases the overall ris