LEARNING THEORY EXPLANATION OF ATTACHMENT

SPECIFICATION: Explanations of attachment: learning theory

THE LEARNING THEORY EXPLANATION OF ATTACHMENT

The basic principle for learning theory put forth by behaviourists is that all behaviour is learned rather than innate. Behaviourists propose an infant’s emotional bond and dependence on the caregiver can be explained through reinforcement, either through classical or operant conditioning.

INTRODUCTION

Before we explore attachment theories, it's essential to understand behaviourism. Although we'll study this approach in detail later, grasping its basic principles now will help us see how it relates to attachment.

BEHAVIOURISM OVERVIEW

Behaviourism, or learning theory, is a psychological approach that began with Ivan Pavlov's work in the early 20th century. It suggests humans are born as "blank slates" (tabula rasa), meaning we don't have built-in personalities or knowledge. Instead, everything we become comes from what we learn through our environment and experiences at home. Behaviourists believe biological factors are unimportant and consider the mind a "black box," implying that internal thoughts are irrelevant and too complex to study scientifically.

There are two main types of behaviourism: classical conditioning and operant conditioning. Some psychologists also include social learning theory as part of behaviourism, but strictly speaking, it sits between behaviourism and the cognitive approach.

Understanding these basic principles of behaviourism will help us see how they apply to attachment theories, which we'll explore next.

There are two main ways behaviourists believe we learn:

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING Learning by associating one thing with another, like Pavlov's dogs learning to associate a bell with food.

OPERANT CONDITIONING: Learning is based on the consequences of our actions, meaning we learn to do things that bring rewards and avoid punishments.

Understanding these basic ideas of behaviourism will help us see how they apply to attachment theories, which we'll explore next.

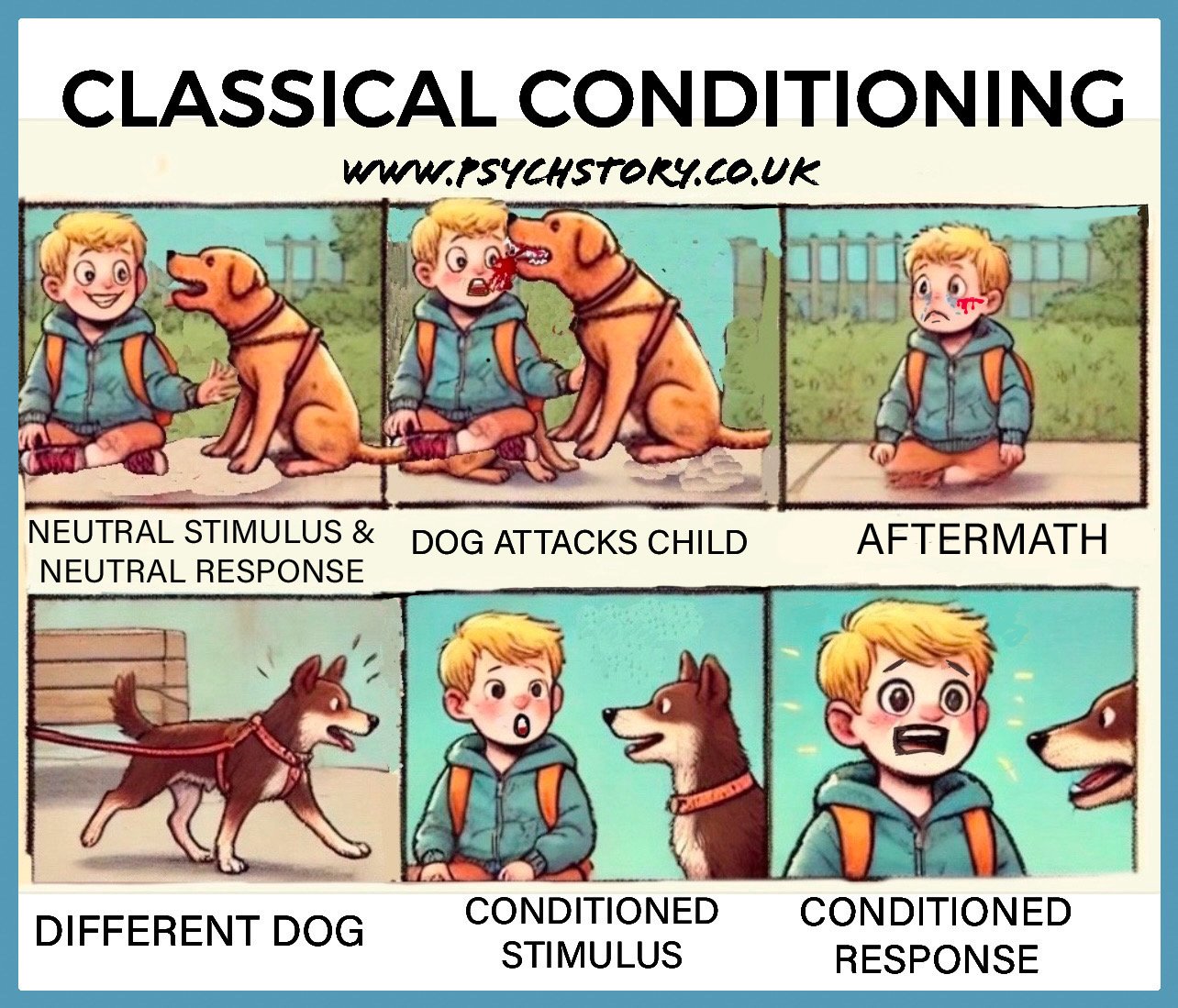

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING

Imagine you have a dog that naturally salivates when it sees food. Now, if you start ringing a bell just before presenting the food, the dog will begin to associate the bell with mealtime. After several repetitions, the dog will start to salivate upon hearing the bell, even if the food isn't present. In this scenario:

UNCONDITIONED STIMULUS (US): The food which naturally causes salivation.

UNCONDITIONED RESPONSE (UR): The dog's salivation in response to the food.

CONDITIONED STIMULUS (CS): The bell, which initially doesn't cause salivation on its own.

CONDITIONED RESPONSE (CR): The dog salivates in response to the bell after learning the association.

This process shows how a neutral stimulus (the bell) can, through association, trigger a response (salivation) that was originally caused by another stimulus (the food)

OPERANT CONDITIONING

Operant conditioning is a learning process where behaviours are influenced by the consequences that follow them. Simply, it's about learning from the results of your actions.

UNDERSTANDING "POSITIVE" AND "NEGATIVE"

In this context, "positive" and "negative" don't mean "good" or "bad." Instead, they're used mathematically:

POSITIVE: Adding something to the situation.

NEGATIVE: Removing something from the situation.

REINFORCEMENT

Reinforcement is used when you want a behaviour to continue or increase. It involves introducing or removing a stimulus to encourage the behaviour.

POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT: Adding something pleasant to encourage a behaviour.

Example: Giving a child a treat for cleaning their room makes them more likely to clean in the future.

NEGATIVE REINFORCEMENT: Removing something unpleasant to encourage a behaviour.

Example: A driver fastens their seatbelt to stop the annoying beeping sound in the car, leading them to use it more regularly.

PUNISHMENT

Punishment is used when you want a behaviour to decrease or stop. It involves introducing or removing a stimulus to discourage the behaviour.

POSITIVE PUNISHMENT: Adding something unpleasant to discourage a behaviour.

Example: Scolding a pet for chewing on shoes makes it less likely to chew them again.

NEGATIVE PUNISHMENT: Taking away something pleasant to discourage a behaviour.

Example: Taking away a teenager's video game time because they missed curfew, aiming to reduce future lateness.

In essence, reinforcement aims to increase behaviours, while punishment aims to decrease them. Understanding these basic principles helps explain how behaviours are learned and modified through environmental interactions.

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING APPLIED TO ATTACHMENT

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING APPLIED TO ATTACHMENT

The learning theory of attachment, primarily influenced by Dollard and Miller (1950), applies Classical Conditioning to explain how infants form emotional bonds with their caregivers. According to this theory, attachment develops as a learned association between the caregiver and the pleasure derived from food rather than being an innate biological process.

Initially, food serves as an unconditioned stimulus (UCS), naturally producing the infant's pleasure (unconditioned response – UCR). The caregiver, initially a neutral stimulus (NS), consistently provides food, leading the infant to associate them with this pleasure. Through repeated pairings, the caregiver becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS), capable of eliciting pleasure (conditioned response – CR) even when feeding is not occurring.

Dollard and Miller further developed this idea by integrating Operant Conditioning, suggesting that attachment is reinforced through reward and discomfort reduction. Hunger creates discomfort (a drive), motivating the infant to seek relief. When the caregiver provides food, the pain is reduced, acting as negative reinforcement for the baby, making them more likely to seek the caregiver in the future. Simultaneously, the caregiver is positively reinforced when responding to the infant's needs, as the baby's contentment strengthens the caregiver’s behaviour.

However, critics such as Harlow (1959) and Schaffer & Emerson (1964) argue that this explanation is overly simplistic, as studies show that infants often form attachments to caregivers even when they do not provide food. This suggests that comfort, security, and responsiveness may play a more significant role in attachment than simple conditioning. Despite its limitations, the learning theory remains influential in understanding how early associations shape emotional bonds.

OPERANT CONDITIONING APPLIED TO ATTACHMENT

Operant Conditioning explains attachment as a learned behaviour shaped by positive and negative reinforcement. Infants learn that their actions influence their environment, and they develop attachment behaviours based on the responses they receive from their caregivers.

Positive Reinforcement – When a behaviour results in a reward, it becomes more likely to be repeated. For example, when an infant cries and their caregiver responds with feeding, cuddling, or attention, the infant learns that crying produces a positive outcome, reinforcing the behaviour.

Negative Reinforcement – When a behaviour removes an unpleasant feeling, it is more likely to be repeated. Hunger causes discomfort, and crying brings the caregiver, who feeds the baby and removes the discomfort. Since crying leads to relief, the infant learns that crying effectively meets their needs.

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY REINFORCERS IN ATTACHMENT

Operant Conditioning also distinguishes between primary reinforcers and secondary reinforcers in attachment formation:

Primary Reinforcer – A stimulus that naturally satisfies a basic need, such as food, warmth, or comfort. Food is the primary reinforcer in attachment, which removes hunger and provides satisfaction.

Secondary Reinforcer – A stimulus associated with a primary reinforcer and eventually gains reinforcing value. In attachment, the caregiver becomes a secondary reinforcer because they are repeatedly associated with feeding and comfort. Over time, the infant learns to seek out the caregiver for food, security, and emotional closeness.

Through this process, the infant develops attachment behaviours, such as crying, smiling, and proximity-seeking, as they learn that their caregiver provides both rewards (positive reinforcement) and relief from discomfort (negative reinforcement). The caregiver’s presence alone becomes rewarding, even when food is not immediately provided, helping to establish a lasting attachment bond.

RESEARCH SUPPORTING BEHAVIOURISM IN ATTACHMENT

While behaviourist explanations of attachment (Classical and Operant Conditioning) have been widely challenged, some research supports the idea that attachment develops through learned associations and reinforcement.

DOLLARD & MILLER (1950) – THE LEARNING THEORY OF ATTACHMENT

Proposed that attachment develops through reinforcement.

Suggested that hunger creates discomfort, which crying alleviates by drawing the caregiver’s attention.

The caregiver feeding the infant acts as negative reinforcement (removing discomfort), strengthening attachment behaviours.

The caregiver also experiences positive reinforcement, as the infant’s contentment encourages continued caregiving.

SCHAAF & TROUP (1974) – INFANT CRYING AND MATERNAL RESPONSE

Found that mothers who responded quickly and consistently to their infant’s crying had children who cried less over time.

Suggests that infants learn through reinforcement that their needs will be met, reducing excessive crying.

This supports Operant Conditioning, as crying is reinforced when it results in care and comfort.

FOGEL (1982) – SOCIAL REINFORCEMENT IN INFANT-CAREGIVER INTERACTIONS

Observed that infants actively engage in behaviours (e.g., cooing, smiling) that elicit positive responses from caregivers.

Caregivers reinforce these behaviours by smiling back, talking, and providing physical affection.

It suggests that attachment develops through mutual reinforcement, supporting operant conditioning and social learning theory.

VESPO ET AL. (1988) – SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY AND ATTACHMENT

Proposed that infants learn attachment behaviours through observation and imitation.

It is found that parents model affectionate behaviours, such as cuddling and smiling, which infants then copy.

Parents also reinforce attachment by rewarding affectionate behaviours in infants with praise and attention.

RESEARCH CHALLENGING BEHAVIOURISM IN ATTACHMENT

HOW HARLOW’S STUDY CHALLENGES BEHAVIOURIST EXPLANATIONS OF ATTACHMENT

Harlow’s research on rhesus monkeys undermines behaviourist attachment theories by demonstrating that comfort and security are more important than food in forming attachments.

Behaviourism suggests that attachment forms through reinforcement, mainly via food as a primary reinforcer. However, Harlow’s monkeys consistently preferred the soft cloth mother over the wire mother that provided food, contradicting the idea that feeding is the key driver of attachment.

If operant conditioning were the primary mechanism, the monkeys would have spent more time with the wire mother, as she was associated with satisfying hunger. Instead, they sought comfort and security from the cloth mother, even when she provided no food.

Similarly, Classical Conditioning assumes that the caregiver becomes a conditioned stimulus through association with feeding. However, the monkeys did not form an attachment to the food-providing wire mother, challenging the idea that attachment is simply a learned association between the caregiver and nourishment.

The study also contradicts Social Learning Theory, as the monkeys did not require modelling or reinforcement to demonstrate attachment behaviours toward the cloth mother. Their preference for comfort appeared innate rather than learned.

Harlow’s findings support Bowlby’s view that attachment is biologically driven and based on the need for emotional security rather than just reinforcement through feeding. This suggests that behaviourist explanations alone are insufficient in explaining the complexities of human attachment.

HOW SCHAFFER & EMERSON (1964) CHALLENGE BEHAVIOURIST EXPLANATIONS OF ATTACHMENT

Schaffer & Emerson’s study contradicts behaviourist theories by demonstrating that attachment is not solely based on feeding or reinforcement but on responsiveness and interaction.

Learning Theory suggests that infants should attach to the person providing food, as feeding is a primary reinforcer. However, Schaffer & Emerson found that in 39% of cases, the mother was not the primary feeder, yet she was still the main attachment figure. This suggests that responsiveness, rather than food provision, is the key factor in attachment formation.

Operant Conditioning predicts that infants will attach to the caregiver who relieves discomfort (e.g., hunger). Yet, the study showed that infants formed their strongest attachment to the most emotionally responsive person, even if they were not feeding them.

Classical Conditioning argues that the caregiver becomes a conditioned stimulus through repeated association with food. However, the study found that attachment was based more on sensitive caregiving and interaction rather than feeding alone, contradicting the idea that attachment is purely learned through association.

The study also found that while infants formed multiple attachments, their strongest bond was always with the mother, even if others, such as the father or grandparents, were more involved in feeding. This undermines the idea that attachment is based on reinforcement through food and supports Bowlby’s view that attachment is driven by emotional security rather than learned associations with nourishment.

EVALUATION OF THE LEARNING THEORY OF ATTACHMENT

OUTDATED AND OVER-SIMPLISTIC

The Learning Theory of attachment, based on Classical and Operant Conditioning, was developed in the mid-20th century when behaviourism dominated psychology. However, modern research suggests that attachment is far more complex than a simple stimulus-response association or reinforcement process. The theory fails to account for cognitive and emotional factors now crucial in attachment formation.

ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATIONS PROVIDE A BETTER ACCOUNT

Bowlby’s Attachment Theory (1969) argues that attachment is innate and biologically programmed, not learned through reinforcement. His concept of monotropy (a primary attachment figure) and the internal working model (a mental template for future relationships) explain long-term emotional and social development, something Learning Theory does not address.

Social Learning Theory (SLT) (Vespo et al., 1988) suggests attachment behaviours are learned through observation and imitation rather than direct reinforcement. Parents model affectionate behaviours (e.g., hugging, smiling), which infants copy. This explanation is more flexible than Learning Theory, as it accounts for the role of social interaction and cognitive processes in attachment.

THAT MIGHT BE PARTIALLY TRUE.

Although the Learning Theory does not fully explain attachment, aspects of reinforcement may still play a role. For example:

Negative reinforcement occurs when an infant cries and the caregiver responds by providing comfort and reinforcing attachment behaviour.

Positive reinforcement happens when caregivers respond to an infant’s needs with affection, strengthening the bond.

However, these mechanisms alone cannot explain the depth of emotional connection between an infant and their caregiver. While behaviourist principles may contribute to attachment, they are not sufficient to fully explain the emotional and biological aspects of early bonding.

CONCLUSION

The Learning Theory of attachment is outdated and reductionist, failing to consider emotional security, cognitive development, and evolutionary influences. Bowlby’s theory and SLT provide more substantial, more comprehensive explanations, as they account for biological predispositions, emotional bonds, and the role of social interactions in attachment formation.

ASSESSMENT

Q1. Annie feeds her newborn baby regularly, forming a strong bond. According to the learning theory of attachment, now she has formed an attachment with her baby, Annie is best described as:

Circle one answer only. (Total one mark)

A conditioned stimulus.A

A neutral stimulus. B

An unconditioned response.C

an unconditioned stimulus. D

Q2. Annie feeds her newborn baby regularly, forming a strong bond.

According to the learning theory of attachment, before any attachment has been formed, the milk Annie gives her baby is best described as:

Circle one answer only. (Total one mark)

A conditioned stimulus.A

A neutral stimulus. B

An unconditioned response.C

an unconditioned stimulus. D

Q3.Describe the learning theory explanation of attachment. (Total four marks)

Q4. Learning theory provides one explanation of attachment. It suggests that attachment will be between an infant and the person who feeds it. However, the findings of some research studies do not support this explanation. Outline research findings that challenge the learning theory of attachment. (Total four marks)

Q5. Outline the learning theory of attachment. (Total four marks)

Q6. Briefly evaluate learning theory as an explanation of attachment. (Total four marks)

Q7. When Max was born, his mother gave up work to stay home and look after him.

Max’s father works long hours and does not have much to do with the day-to-day care of his son. Max is nine months old and has a close bond with his mother. Use learning theory to explain how Max became attached to his mother rather than to his father. (Total six marks)

Q8. Outline and evaluate the learning theory of attachment. (Total eight marks)

Q9. Psychologists have proposed different explanations for attachment, such as learning theory and Bowlby’s theory. Outline and evaluate one or more explanations of attachment. (Total twelve marks)

Q10. Discuss the learning theory explanation of attachment (sixteen marks)

Q11. Two mothers in the toddler and parent group are chatting. “I always felt sorry for my husband when Millie was a baby. He used to say his bond with Millie was not as strong as mine because I was breastfeeding.“I’m not sure”, replies the other mother. “I think something about a mother’s love makes it more special anyway – and so important for future development.” Discuss the learning theory of attachment and Bowlby’s monotropic theory of attachment. Refer to the conversation above in your answer. (Total sixteen marks)